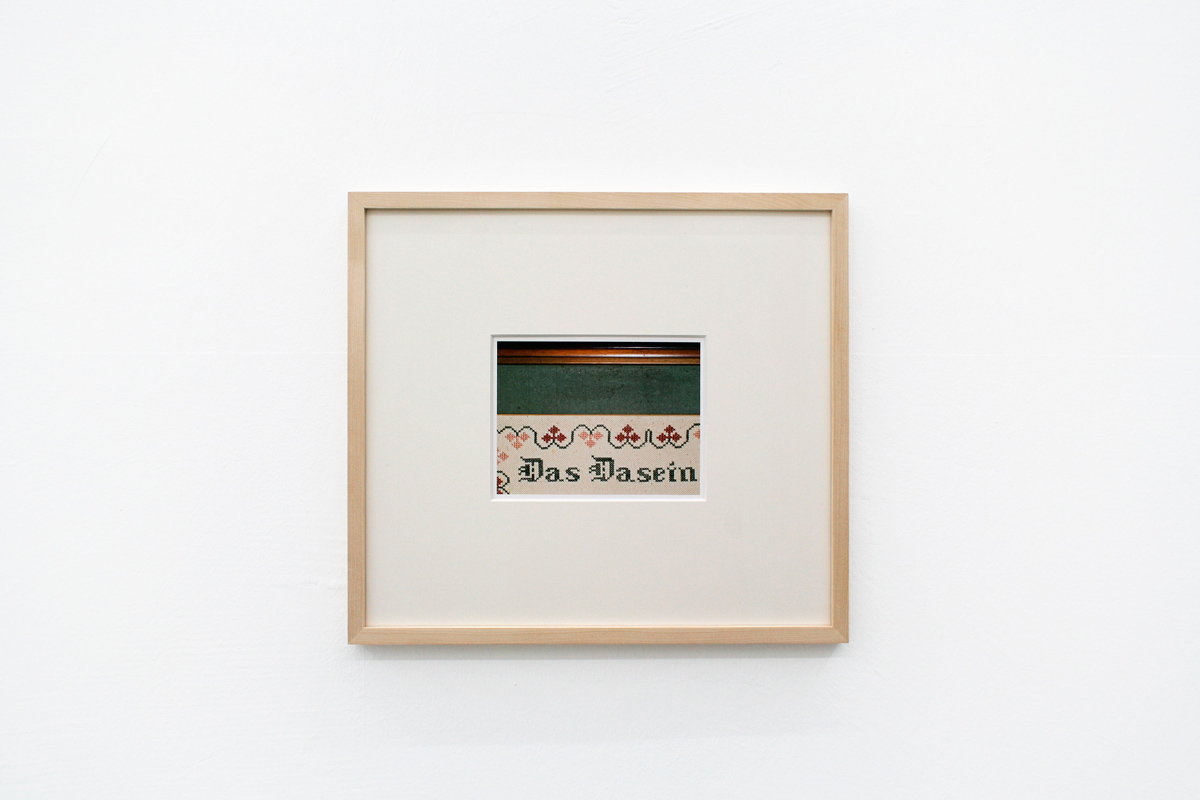

UNTITLED (DAS DASEIN)

Inkjet on Hahnemühle Photo Rag (305g)

16 x 12 cm

UNTITLED (SCHWARZENBERG)

Leather

27 x 11 x 55 cm

THE HOLEBURY (PEDESTAL)

Woodcut with bronze letters

Oil block printing ink on Arches paper (308g satin)

113 x 149 cm

ACT ZERO

Video 720p, 9 min

Size variable

MOBY DICK

Animation, Full HD, Loop

Size variable

UNTITLED (COMMON HORSEFLY)

Gold

1,4 x 1 x 0,6 cm

UNTITLED (BEEHIVE)

Oil on canvas

4 paintings, each 50 x100 cm

THE HOLBURY (SCRIPT)

Chair, manuscript, rock

42 x 45 x 75 cm

Act Zero is Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen’s second solo show at KROME Gallery. Speaking as a translator, the Norwegian artist conveys his experiences of a two month journey he undertook on foot, from Berlin to Trieste, in the summer of 2011. At the same time, observations he gleaned from the process of translating Le Bétrou, a play by the French dadaist Julien Torma, form a common thread in the exhibition.

The title of the show, Act Zero, is taken from the last act of this four act play, which starts at minus three and culminates with act zero. “Le Bétrou” itself is a strange creature who instils terror in the other characters of the play, though he is only capable of speaking in inarticulate stammers and his utterances have to be interpreted by an astronomer. In the last act of the play, he finally manages to produce some animal noises, but this only diminishes his power. The veil of abstraction upon which a dominant language depends is lifted, revealing the uncertainty of language and representation when these are stripped of their context.

It was only through translating the play that Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen was able to fully comprehend the surreal diversity of the text. In this way, the mere act of reading became an investigative, linguistic journey. The woodcut with the bronze lettering in the front room of the gallery is a direct expression of the act of translation. “Holebury” is a literal translation of the homophonic play from which Torma derived the non-existent word “Bétrou”. Holebury, an old spelling of an actual English surname and place name, brings us back to the realm of the real. But through an uncanny contingency, the meaning of this name – “hollow fortification” – points to the way a dominant language only serves to conceal an underlying lack and evaporates when confronted by doubt. This revelation is compounded by the circular notion of the name itself: dig a hole, bury, dig a hole, bury, …

The Holebury (pedestal) builds on this translation while also representing the central element of the stage set from the final act: a pedestal with the name “The Holbury” in gleaming gold letters. The character Holebury is to be inaugurated as a statue, and just as he is about to climb the pedestal and merge with this image of power, the other characters chase him away and the play ends in chaos, or a certain degree of nothingness. The pedestal remains empty until the last sentence of the last scene in the last act: “A ridiculous, egg-juggling squirt of water then emerges from the empty pedestal.”

The Holbury (pedestal) and the film Act Zero consummate this image. In the latter, a film shot using a high-speed camera, we are presented with an egg balanced on a jet of water. While working on the play Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen happened to come across this same image in two other books by the surrealist writers Philippe Soupault and Robert Desnos. And during further research into the image he found that a number of other surrealist writers and artists had also used it: Rene Clair and Francis Picabia in their film Entr’acte (Between Acts), Henry Miller in his Tropic of Cancer and Jean Cocteau in his poem ILES. The origin of the image seems to go back to the sixteenth century, when the acolytes at Barcelona Cathedral would place eggs on the cloister’s fountain during the festival of Corpus Christi. In the nineteenth century it became a popular fairground game, the aim being to shoot the dancing eggs off the jets of water with air rifles. Having initially been curious about the symbolism of the ending of Torma’s play, Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen then became fascinated by the multifarious uses and metaphors of this egg image, which suggests everything from religion to capitalism, death, sex and love. The image became a model of the semantic diversity of language: its endless references bring it back to the concrete image; an image of pure potentiality.

After writing Le Bétrou Torma gave up on literature for a life of perpetual drifting, which ended when he disappeared while hiking in the Austrian Alps. The ideas behind Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen’s journey were similar; he wanted to leave art behind for a while to just concentrate on being. In order to avoid the question of exactly where to go he decided to set himself one rule: to walk south. Rather than being guided by any desire to visit places of particular interest, his route was determined by a certain controlled randomness. He was interested in seeing the in-between places that one never really gets to see when travelling from one place to another by other means of transportation. But even when an artist chooses not to make art, his gaze is still that of an artist, and when he came back there were some fragments that had stayed with him, a succession of moments that seemed to combine both reality and some sort of relation to more artistic or philosophical concerns.

The photo Untitled (Das Dasein) may be taken as a first instance of this: it is a detail from a typical proverb embroidery found in a restaurant in the Austrian Alps. The only visible words are “Das Dasein”, which literally means “being there” in English, but it is also a fundamental concept in the existential philosophy of Martin Heidegger, particularly in his book Being and Time. The photo is the only picture which directly represents the journey, and in a sense it merely rehearses the romantic notion of the hiker dwelling in the here and now. But at the same time it manages to set up a dialectic between existence (everyday life) and existentialism, and as a representation it portrays the possibility of representation, suggesting both utopia and possible failure. In a similar way, Untitled (Moby Dick) plays with the real and the fantastic. Moby Dick was the one book Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen took with him on his trip, but here it is represented by an animation created from a piece of toilet paper he found in a restroom when he first stopped for food somewhere in the outskirts of Berlin. The picture printed on the piece of paper showed three whales: one emerging from the water, one just on the surface and one diving. For the rest of the trip it served as a bookmark, a whale within the whale, a voyage within the voyage, and a reflection within the reflection.

With the sculpture Untitled (Schwarzenberg) Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen transposes a detail from an early nineteenth-century painting into present-day reality. At Orlik Castle in the Czech Republic – formerly the hunting lodge of Field Marshal Karl Philipp Fürst zu Schwarzenberg – he saw a portrait by one of Napoleon’s court painters. Schwarzenberg is shown wearing a pair of boots, though he has chosen to censor them by having another artist repaint them. What used to be a pair of rounded French riding boots was transformed into a straight-cut German-style boot. After the Peace of Vienna Schwarzenberg was sent to Paris to negotiate Napoleon’s marriage to Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria. Napoleon, a great admirer of Schwarzenberg, then requested that the prince take command of the Austrian auxiliary corps in the Russian campaign of 1812. But when Austria then took the side of the allies against Napoleon in 1813, Schwarzenberg was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the allied Grand Army of Bohemia which went on to defeat Napoleon. History seems to be contained in this minute gesture – the cut of the boots, as an illusion of fashion, conceals reality like a trick of the light. But what is there is still there, underlining the conflict between personal vanity and reality in the construction of a personal truth in the folds of history.

Untitled (Beehive), a series of four paintings, plays with the idea of reference. The patterns are copies of paintings on a beehive Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen encountered somewhere in the Czech Republic on his journey from Berlin to Trieste. At first glance the images evoke a specific style of art, but this reference remains quite empty and the viewer is tempted to read too much into the paintings, for the originals were not created in the context of artistic design.

Untitled (Common Horsefly) is perhaps the most inconspicuous work in the exhibition: a gold rendering of a female pluvial haematopota, or common horsefly. This type of insect accompanied Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen on many days of his journey. There is a certain irony in the fact that this irritating, bloodsucking insect is represented in gold. It is at once a portrait of a problem and, ultimately, the thing that keeps you in touch with reality, saving you from generalizations and preconceived ideas by keeping you in the flux of doubt.

Symbolic metaphors, iconic referencing and the arbitrariness of language pervade the entire exhibition in the form of dialectical coincidences. The works originate in the accomplishment of two journeys – the one hiking on foot, the other in the act of translation. The theme of distance is reflected on several levels. The distances that Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen covered during his journey also evoke a mental distance, a distancing attitude towards things past. It is precisely this attitude which is necessary for a successful translation. Without the requisite impartiality there would be a shift in interpretation and the translation process would remain incomplete. The mediation between reality and its representation would risk irrevocable disruption at the hands of failure.

Act Zero is Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen’s second solo show at KROME Gallery. Speaking as a translator, the Norwegian artist conveys his experiences of a two month journey he undertook on foot, from Berlin to Trieste, in the summer of 2011. At the same time, observations he gleaned from the process of translating Le Bétrou, a play by the French dadaist Julien Torma, form a common thread in the exhibition.

The title of the show, Act Zero, is taken from the last act of this four act play, which starts at minus three and culminates with act zero. “Le Bétrou” itself is a strange creature who instils terror in the other characters of the play, though he is only capable of speaking in inarticulate stammers and his utterances have to be interpreted by an astronomer. In the last act of the play, he finally manages to produce some animal noises, but this only diminishes his power. The veil of abstraction upon which a dominant language depends is lifted, revealing the uncertainty of language and representation when these are stripped of their context.

It was only through translating the play that Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen was able to fully comprehend the surreal diversity of the text. In this way, the mere act of reading became an investigative, linguistic journey. The woodcut with the bronze lettering in the front room of the gallery is a direct expression of the act of translation. “Holebury” is a literal translation of the homophonic play from which Torma derived the non-existent word “Bétrou”. Holebury, an old spelling of an actual English surname and place name, brings us back to the realm of the real. But through an uncanny contingency, the meaning of this name – “hollow fortification” – points to the way a dominant language only serves to conceal an underlying lack and evaporates when confronted by doubt. This revelation is compounded by the circular notion of the name itself: dig a hole, bury, dig a hole, bury, …

The Holebury (pedestal) builds on this translation while also representing the central element of the stage set from the final act: a pedestal with the name “The Holbury” in gleaming gold letters. The character Holebury is to be inaugurated as a statue, and just as he is about to climb the pedestal and merge with this image of power, the other characters chase him away and the play ends in chaos, or a certain degree of nothingness. The pedestal remains empty until the last sentence of the last scene in the last act: “A ridiculous, egg-juggling squirt of water then emerges from the empty pedestal.”

The Holbury (pedestal) and the film Act Zero consummate this image. In the latter, a film shot using a high-speed camera, we are presented with an egg balanced on a jet of water. While working on the play Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen happened to come across this same image in two other books by the surrealist writers Philippe Soupault and Robert Desnos. And during further research into the image he found that a number of other surrealist writers and artists had also used it: Rene Clair and Francis Picabia in their film Entr’acte (Between Acts), Henry Miller in his Tropic of Cancer and Jean Cocteau in his poem ILES. The origin of the image seems to go back to the sixteenth century, when the acolytes at Barcelona Cathedral would place eggs on the cloister’s fountain during the festival of Corpus Christi. In the nineteenth century it became a popular fairground game, the aim being to shoot the dancing eggs off the jets of water with air rifles. Having initially been curious about the symbolism of the ending of Torma’s play, Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen then became fascinated by the multifarious uses and metaphors of this egg image, which suggests everything from religion to capitalism, death, sex and love. The image became a model of the semantic diversity of language: its endless references bring it back to the concrete image; an image of pure potentiality.

After writing Le Bétrou Torma gave up on literature for a life of perpetual drifting, which ended when he disappeared while hiking in the Austrian Alps. The ideas behind Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen’s journey were similar; he wanted to leave art behind for a while to just concentrate on being. In order to avoid the question of exactly where to go he decided to set himself one rule: to walk south. Rather than being guided by any desire to visit places of particular interest, his route was determined by a certain controlled randomness. He was interested in seeing the in-between places that one never really gets to see when travelling from one place to another by other means of transportation. But even when an artist chooses not to make art, his gaze is still that of an artist, and when he came back there were some fragments that had stayed with him, a succession of moments that seemed to combine both reality and some sort of relation to more artistic or philosophical concerns.

The photo Untitled (Das Dasein) may be taken as a first instance of this: it is a detail from a typical proverb embroidery found in a restaurant in the Austrian Alps. The only visible words are “Das Dasein”, which literally means “being there” in English, but it is also a fundamental concept in the existential philosophy of Martin Heidegger, particularly in his book Being and Time. The photo is the only picture which directly represents the journey, and in a sense it merely rehearses the romantic notion of the hiker dwelling in the here and now. But at the same time it manages to set up a dialectic between existence (everyday life) and existentialism, and as a representation it portrays the possibility of representation, suggesting both utopia and possible failure. In a similar way, Untitled (Moby Dick) plays with the real and the fantastic. Moby Dick was the one book Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen took with him on his trip, but here it is represented by an animation created from a piece of toilet paper he found in a restroom when he first stopped for food somewhere in the outskirts of Berlin. The picture printed on the piece of paper showed three whales: one emerging from the water, one just on the surface and one diving. For the rest of the trip it served as a bookmark, a whale within the whale, a voyage within the voyage, and a reflection within the reflection.

With the sculpture Untitled (Schwarzenberg) Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen transposes a detail from an early nineteenth-century painting into present-day reality. At Orlik Castle in the Czech Republic – formerly the hunting lodge of Field Marshal Karl Philipp Fürst zu Schwarzenberg – he saw a portrait by one of Napoleon’s court painters. Schwarzenberg is shown wearing a pair of boots, though he has chosen to censor them by having another artist repaint them. What used to be a pair of rounded French riding boots was transformed into a straight-cut German-style boot. After the Peace of Vienna Schwarzenberg was sent to Paris to negotiate Napoleon’s marriage to Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria. Napoleon, a great admirer of Schwarzenberg, then requested that the prince take command of the Austrian auxiliary corps in the Russian campaign of 1812. But when Austria then took the side of the allies against Napoleon in 1813, Schwarzenberg was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the allied Grand Army of Bohemia which went on to defeat Napoleon. History seems to be contained in this minute gesture – the cut of the boots, as an illusion of fashion, conceals reality like a trick of the light. But what is there is still there, underlining the conflict between personal vanity and reality in the construction of a personal truth in the folds of history.

Untitled (Beehive), a series of four paintings, plays with the idea of reference. The patterns are copies of paintings on a beehive Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen encountered somewhere in the Czech Republic on his journey from Berlin to Trieste. At first glance the images evoke a specific style of art, but this reference remains quite empty and the viewer is tempted to read too much into the paintings, for the originals were not created in the context of artistic design.

Untitled (Common Horsefly) is perhaps the most inconspicuous work in the exhibition: a gold rendering of a female pluvial haematopota, or common horsefly. This type of insect accompanied Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen on many days of his journey. There is a certain irony in the fact that this irritating, bloodsucking insect is represented in gold. It is at once a portrait of a problem and, ultimately, the thing that keeps you in touch with reality, saving you from generalizations and preconceived ideas by keeping you in the flux of doubt.

Symbolic metaphors, iconic referencing and the arbitrariness of language pervade the entire exhibition in the form of dialectical coincidences. The works originate in the accomplishment of two journeys – the one hiking on foot, the other in the act of translation. The theme of distance is reflected on several levels. The distances that Tarje Eikanger Gullaksen covered during his journey also evoke a mental distance, a distancing attitude towards things past. It is precisely this attitude which is necessary for a successful translation. Without the requisite impartiality there would be a shift in interpretation and the translation process would remain incomplete. The mediation between reality and its representation would risk irrevocable disruption at the hands of failure.